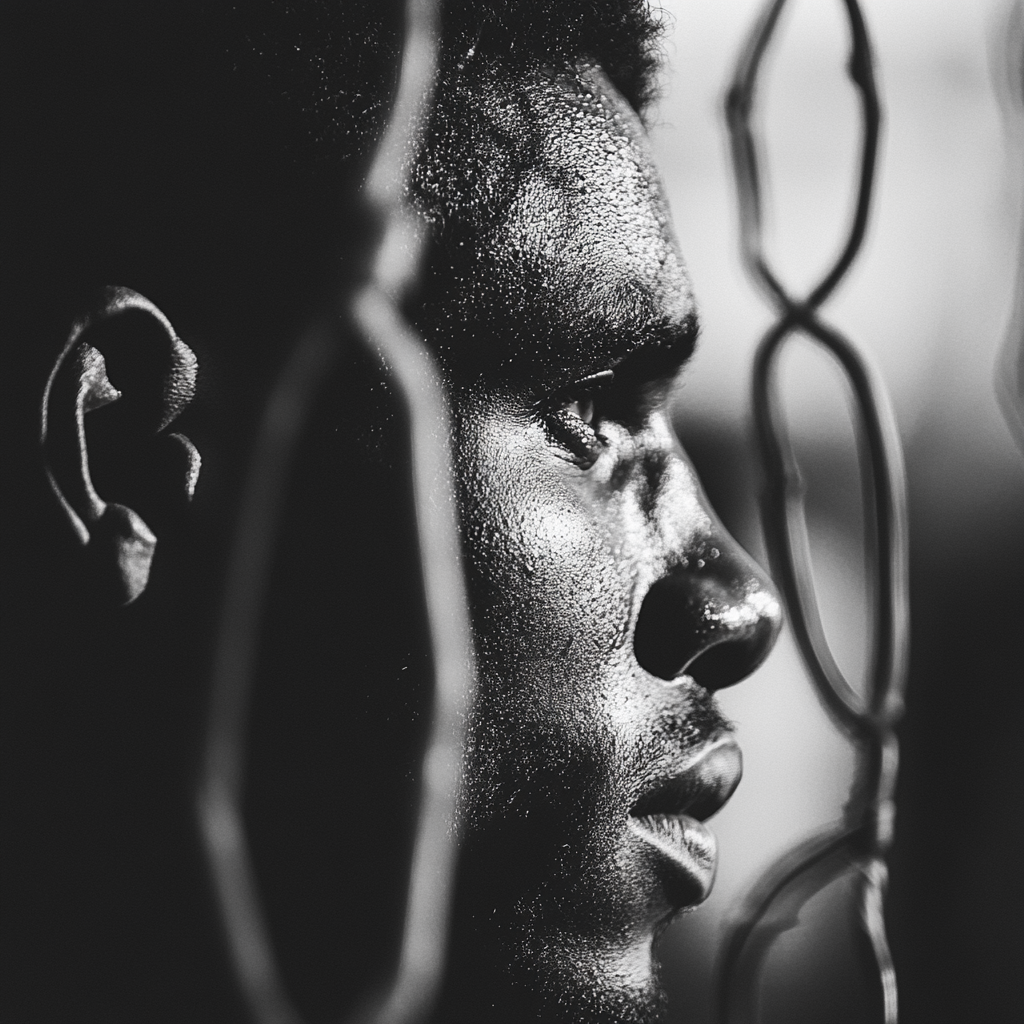

Introduction: Queensland’s youth justice system is under intense scrutiny amid high reoffending rates and public concern about youth crime. In recent data, 91% of young people released from Queensland detention returned within 12 months (LNP - Liberal National Party of Queensland (LNP)) – the highest recidivism in Australia. In response, the state’s Making Queensland Safer plan (a 2024 election platform) introduced two major grant-funded initiatives: “Staying on Track” and “Regional Reset.” These programs, budgeted at $175 million and $50 million over four years respectively (Youth Justice Power Point Presentation) (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf), aim to rehabilitate at-risk youth through intensive support and early intervention. This report examines how these grants are structured and how they could be better deployed to empower grassroots community solutions in youth justice. It also analyses the risks of large organisations monopolising funds, compares youth justice funding models in Spain and Scotland, reviews cost-effectiveness (administration vs. frontline investment), and outlines policy recommendations to maximise community impact.

1. Funding Allocation and Community Impact

Current Structure and Distribution: The Staying on Track program is designed as a post-detention rehabilitation scheme for every youth leaving detention (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf) (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf). Under this model, a community service provider is paired with each young person while they are still in custody, then continues to mentor and support them for 12 months after release (LNP - Liberal National Party of Queensland (LNP)). Every young offender gets a tailored “Successful Release Plan” with goals around education, training, work and positive activities (e.g. schooling or TAFE, driving lessons, mentoring, sports) (LNP - Liberal National Party of Queensland (LNP)). The funding – roughly $43–45 million per year (from the $175m/4yrs) – is being split into regional service hubs. A recent procurement brief shows 12 regional hubs across Queensland, each with a specified annual allocation (for example, about $6.98 million per year for the Townsville/Mackay hub serving ~130 youths) (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf) (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf). The largest hubs (Townsville, Cairns, Ipswich/West Moreton) have ~$6–7 million per year, while smaller areas (e.g. Cherbourg) have under $1 million (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf). Notably, for several hubs the government “prefers Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander suppliers” (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf) (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf) – an attempt to engage Indigenous-led organizations for communities with high First Nations youth representation.

The Regional Reset program is a complementary early intervention initiative. It establishes nine short-term residential “reset” camps (1–3 week live-in programs) across the state (LNP - Liberal National Party of Queensland (LNP)) (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf). Each camp will serve a broad region (Far North, North, Central, Wide Bay, Western Qld, etc.), aligning with the areas announced in the policy (LNP - Liberal National Party of Queensland (LNP)) (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf). The $50 million fund (over 4 years) covers all nine sites (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf). The program targets children 8–17 years old who exhibit serious risk factors (violence, truancy, substance abuse) but may not yet be entrenched in crime (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf). Youth can be referred by schools, police, child safety or parents. Each Regional Reset center provides an intensive supervised environment – described as a “circuit-breaker” for “out-of-control youths” (LNP - Liberal National Party of Queensland (LNP)) – focused on life skills, self-discipline, counseling, and cultural or adventure activities (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf). Importantly, the model isn’t just a short camp: it includes pre-camp engagement with the family, the live-in reset, and follow-up aftercare with mentoring and referrals in the community (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf) (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf). A cross-agency/community referral panel in each location will triage which youth attend the program (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf). By design, Regional Reset “works hand-in-hand” with other initiatives like the Gold Standard Early Intervention and Youth Justice “academy” schools (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf), forming an integrated early intervention network.

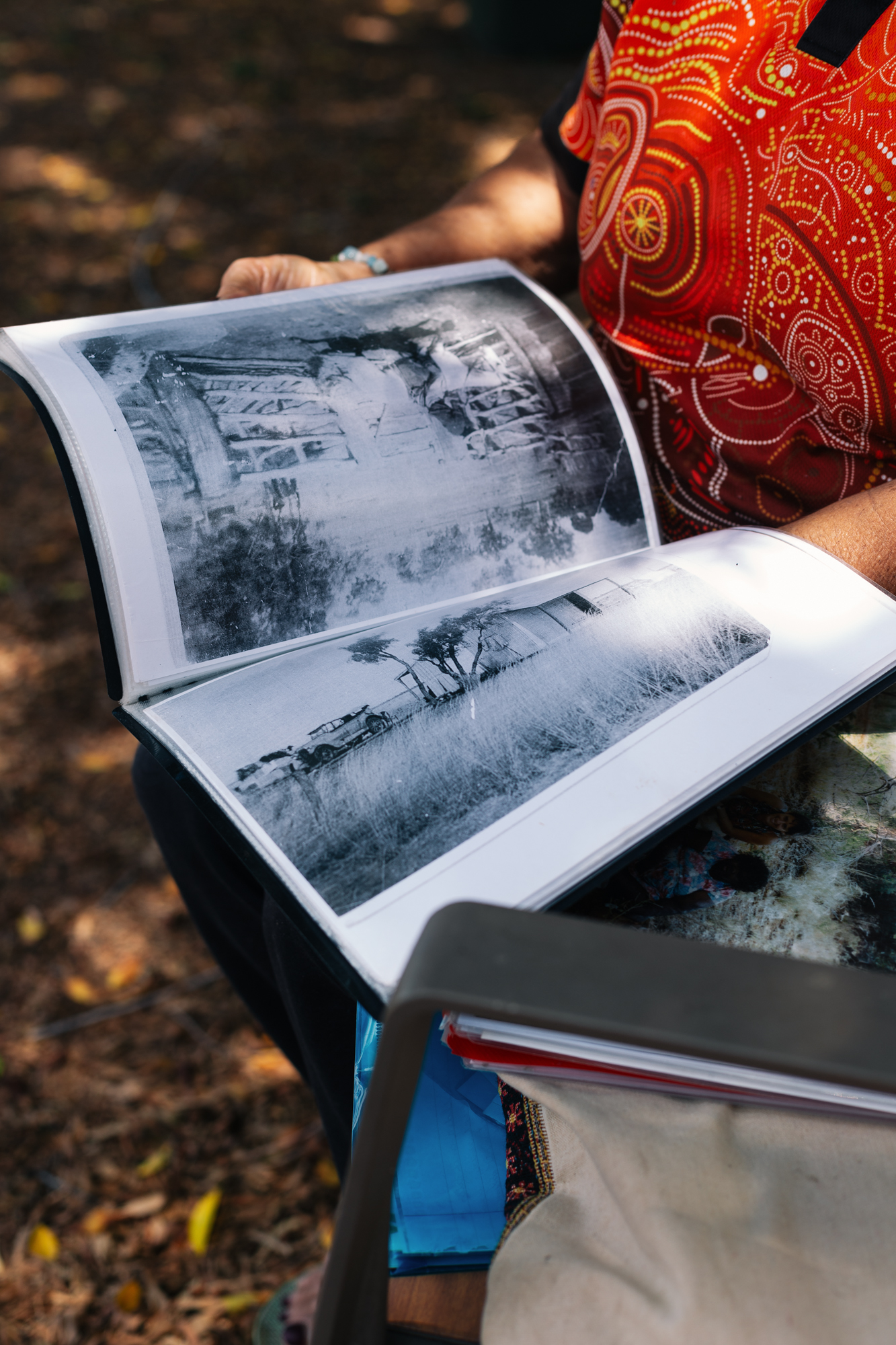

Reallocating Funds to Grassroots for Local Impact: While these programs are substantial investments, their impact will depend on who delivers the services. There is a strong case for channeling funds to grassroots and community-based organisations rather than relying solely on large central providers. Grassroots groups – local youth services, Indigenous community organisations, volunteer-driven clubs, etc. – are often deeply embedded in the community and can engage high-risk youth with greater credibility, cultural relevance, and trust. For example, Queensland’s tender for Staying on Track explicitly allows partnerships or consortiums so providers can cover large catchments (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf) (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf). This creates an opportunity for big NGOs to partner with smaller local groups, or for regional coalitions of community orgs to bid. Priority regions like Cairns, Mount Isa, Cherbourg have encouraged Indigenous-led bids (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf) (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf), recognizing that local Aboriginal-run services may connect better with Indigenous youth (who form a majority of those in the justice system). By reallocating a significant portion of grant funding to on-the-ground community partners, the programs can leverage local knowledge and relationships. For instance, instead of one large agency running a Regional Reset camp with fly-in staff, the funding could support a collaboration of local elders, youth workers and counsellors from that region. This grassroots approach ensures interventions are tailored to local context (language, culture, community dynamics) and that communities have ownership of solutions.

Research strongly supports the effectiveness of community-led solutions in youth justice. Around the world, keeping youth in their communities under supportive supervision leads to better outcomes than incarceration (Effective Alternatives to Youth Incarceration – The Sentencing Project). In Queensland, the Youth Justice Commissioner observed that community-based youth justice is not only more successful in changing behavior, but also far cheaper than detention – costing about 10 times less per child (). Diversionary and rehabilitative programs driven by community actors can significantly cut reoffending. A meta-analysis of 29 trials found that formal justice responses made reoffending more likely than diversion programs, and police-led cautions/diversions achieved lower reoffending (44% vs 50%) than court processing (). European countries favour cognitive-behavioural programs delivered in community settings over punitive measures, precisely because punitive approaches often increase recidivism (). Empowering community organisations to address underlying issues – family dysfunction, trauma, disengagement – can break the cycle of crime more effectively. These local groups often take a holistic approach (mentoring, cultural reconnection, education support, family mediation) that addresses the causes of offending, not just the symptoms. In sum, investing grant funds at the grassroots level can maximise local impact: it not only strengthens community capacity but also increases the chances that young people will respond positively, seeing familiar faces and culturally appropriate support instead of distant authority figures. Every dollar spent on a community-led program is likely to yield higher social returns in terms of reduced crime and improved youth outcomes.

2. Risks of Large Organisations Dominating Funding

Concentration of Funding in Large NGOs: A potential pitfall in the rollout of Staying on Track and Regional Reset is if the funding is captured mainly by large NGOs or government-aligned organisations, rather than distributed among smaller community providers. Major non-government organisations (NGOs) – often charities or corporate service providers – have the capacity to bid for multi-million-dollar contracts across multiple regions. However, when big organizations dominate funding, certain risks emerge. First, it can crowd out grassroots initiatives: smaller groups may lack the resources to compete in procurement processes, so the same big players get funded repeatedly. Queensland’s Auditor-General noted that in recent years the department sometimes renewed or procured services without adequately testing the market or justifying provider choices (Reducing serious youth crime | Queensland Audit Office) (Reducing serious youth crime | Queensland Audit Office). This raises the risk that funding decisions become insular, favouring established vendors rather than the most effective local solutions. If Staying on Track’s 12 regional contracts, for example, were all won by a handful of large NGOs, the program could end up operating top-down with a one-size-fits-all model, instead of the intended community-tailored approach.

Administration vs Direct Community Impact: Large organisations often have significant administrative overheads that can siphon funding away from frontline services. These NGOs maintain centralised offices, management staff, marketing and governance structures that smaller grassroots groups do not. While some larger charities are efficient (e.g. Save the Children Australia reports about 81% of spending on programs vs ~7% on admin (What Percentage of Donation Goes to Charity)), investigations show others have very high overhead. In Australia, certain well-known charities have been found to spend over half of their income on administration and fundraising (Giving Guide | The Overhead Myth). In a youth justice context, a big provider might use grant funds to cover layers of project managers, analysts, and corporate costs – meaning perhaps only a fraction reaches the youth workers and mentors on the ground. By contrast, a small local youth service might dedicate nearly every dollar to direct support (with maybe a volunteer board and minimal admin). Excessive administrative spending dilutes community impact: for example, if a $1 million grant is delivered by a bureaucratic agency with 30% overhead, that’s $300k lost to paperwork and salaries that never interact with youth. There is also the risk of bureaucratic inertia – large institutions may be less agile in responding to individual needs. Community members sometimes complain that big agencies come with preset programs and heavy reporting requirements, rather than adapting to what the community knows works. In youth justice, building rapport quickly with vulnerable teens is critical; a small grassroots team might achieve that through informal, relationship-based practice, whereas a big NGO might be more constrained by protocols.

Bureaucratic Inefficiencies and Leakage: Government-aligned or internal government delivery can likewise suffer from bureaucratic inefficiency. Funds can get tied up in lengthy planning, coordination meetings, and inter-departmental processes before services reach young people. In Queensland’s youth justice system, multiple agencies and levels of approval are often involved ([PDF] Changes to the youth justice system must be designed and ...). This complexity can slow down initiative rollout. The new grants themselves require oversight – for instance, the department will monitor providers via an online reporting system and formal evaluations (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf) (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf). While accountability is important, overly onerous compliance can divert provider effort to paperwork over practice. The challenge is ensuring that the substantial investments “at the top” quickly translate to action at the grassroots. Queensland Audit Office findings underline this: the youth justice department was not effectively evaluating outcomes data provided by NGOs (Reducing serious youth crime | Queensland Audit Office), meaning money was spent without learning what worked. Additionally, some large contracts were managed with minimal documentation of why that provider was chosen (Reducing serious youth crime | Queensland Audit Office), which could mask under-performance. All these inefficiencies ultimately reduce the tangible benefit felt in communities.

Ensuring Funds Reach the Ground: To mitigate these risks, specific strategies must accompany the grants. Transparency in funding allocation is key – publishing which organisations receive funds and how much reaches direct services. Caps or guidelines on allowable administrative costs can be imposed in contracts (for example, requiring that at least 80–90% of funds go to service delivery costs). Queensland’s procurement for Staying on Track encourages consortium bids (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf) – this could be leveraged to pair large NGOs (with financial/admin capacity) with grassroots groups (with local credibility), thus combining strengths and ensuring money flows down to community sub-partners. Another solution is outcome-based contracting, which Queensland is moving toward: providers are paid based on outcomes achieved (e.g. reductions in reoffending, education engagement), not just outputs or budget spent (Reducing serious youth crime | Queensland Audit Office). This model incentivises efficiency and ground-level impact, though outcomes must be measured carefully. The department can also ring-fence a portion of the funding specifically for small community-led projects (for instance, through micro-grants or a “Kickstarter Grants” scheme already signaled under the early intervention plan (Our commitments | Department of Youth Justice and Victim Support)). By dedicating funding streams for grassroots initiatives, large organisations are prevented from swallowing the entire pie. Finally, robust oversight and evaluation will ensure big providers don’t under-deliver – regular audits, community feedback loops, and public reporting on youth outcomes per dollar spent will shine a light on whether funds truly reach those working on the ground. In sum, a conscious effort must be made to avoid bureaucratic capture of these grants. When community groups are resourced and empowered, the initiatives can fulfil their promise of locally led change; if not, they risk becoming just another program managed from Brisbane offices with little tangible change on the street.

3. Comparative Analysis – Spain and Scotland

Queensland can learn much from how Spain and Scotland fund and support youth justice initiatives, as both have pioneered community-centric, rehabilitative models that contrast with Australia’s more punitive systems.

Spain’s Model – Rehabilitation through Community-Run Centres: Spain is often cited as a youth justice success story for its emphasis on education, reintegration, and community-based rehabilitation. Under Spain’s Juvenile Justice Act, the focus is on individualised educational measures rather than punishment. Many of Spain’s youth justice facilities are operated by non-profit foundations (e.g. Fundación Diagrama) in partnership with government, but with a philosophy of care that mirrors a community setting (From Punishment to Potential: Lessons from Spain's Innovative Youth Justice Model - Day 1 with Diagrama) (From Punishment to Potential: Lessons from Spain's Innovative Youth Justice Model - Day 1 with Diagrama). Facilities are generally small-scale (some as small as 12 beds) and normalised – staff in casual clothes, a school-like atmosphere – to avoid the feel of prisons (From Punishment to Potential: Lessons from Spain's Innovative Youth Justice Model - Day 1 with Diagrama) (From Punishment to Potential: Lessons from Spain's Innovative Youth Justice Model - Day 1 with Diagrama). The approach is therapeutic and relationship-based: youth build trust with staff who act as mentors and teachers, and activities include schooling, vocational training, sports, arts, and family visits (From Punishment to Potential: Lessons from Spain's Innovative Youth Justice Model - Day 1 with Diagrama) (From Punishment to Potential: Lessons from Spain's Innovative Youth Justice Model - Day 1 with Diagrama). Crucially, programs are tailored to local cultures in Spain’s diverse regions (From Punishment to Potential: Lessons from Spain's Innovative Youth Justice Model - Day 1 with Diagrama) and maintain strong links to the community (through outings, community service, etc.). This model has achieved remarkable outcomes. Recidivism rates in Spain are far lower than in Queensland – one study found only 13.6% of youths released from Diagrama centres in Murcia reoffended within six years (From Punishment to Potential: Lessons from Spain's Innovative Youth Justice Model - Day 1 with Diagrama). This is a fraction of Queensland’s reoffending rate. The Diagrama program alone has helped over 40,000 young people since 1991 with a “significantly lower recidivism rate than typical” (From Punishment to Potential: Lessons from Spain's Innovative Youth Justice Model - Day 1 with Diagrama) (From Punishment to Potential: Lessons from Spain's Innovative Youth Justice Model - Day 1 with Diagrama). Funding mechanisms in Spain differ as well: because youth detention is seen as an education/welfare matter, resources are allocated to staffing schools, psychologists, and social educators rather than to security. As a result, costs per detainee are much lower than in Australia – about €70,000 (≈A$110,000) per youth annually in Spain versus over $1 million per youth annually in Australia (A Comparative Analysis of Youth Justice Systems in Spain and Australia). In other words, Spain achieves far better outcomes at roughly one-tenth the cost per young offender. The key is that money is invested in human services (teachers, therapists, community integration) instead of heavy infrastructure or incarceration. Spain also heavily utilises alternatives to custody such as community service, mediation with victims, and supervised release, meaning custody is truly a last resort. This fosters a system where community-led interventions (like restorative justice programs) are the norm, and institutional placement is rare. The Spanish experience shows that a rehabilitative, community-integrated approach can dramatically cut reoffending and save costs, by funding what actually works – support, not punishment (A Comparative Analysis of Youth Justice Systems in Spain and Australia).

Scotland’s Model – Community Justice and Early Intervention: Over the past 15 years, Scotland has transformed its youth justice system through policies that empower communities and stress prevention. A cornerstone is the Children’s Hearings System, a unique model in which panels of trained community volunteers make decisions on cases of children who offend or are in need of care. This system, rooted in the Kilbrandon Report’s welfare philosophy, treats child offenders “as children first” and emphasises addressing underlying needs over punitive measures (A Guide to Youth Justice in Scotland: policy, practice and legislation) (A Guide to Youth Justice in Scotland: policy, practice and legislation). Most youth cases in Scotland are diverted to these community hearings rather than formal courts, ensuring a community-led, restorative approach (families and the child participate in defining solutions). In terms of funding, Scotland has embraced a “Whole System Approach” (WSA) to youth crime since 2011, which coordinates police, social services, schools, and community organisations to intervene early and keep youth out of custody. The government directly supports local authority youth justice teams and partners – for example, an extra £1.6 million was allocated to councils over 2018–2020 to strengthen early intervention up to age 21 (and 26 for care-leavers) (Extra funding announced to prevent youth offending | Law Society of Scotland) (Extra funding announced to prevent youth offending | Law Society of Scotland). Investments like these have paid off dramatically: Scotland saw a 78% drop in the number of under-18s prosecuted in court from 2006–2018, and a 66% reduction in the number of young people in custody (Extra funding announced to prevent youth offending | Law Society of Scotland) (Extra funding announced to prevent youth offending | Law Society of Scotland). This coincided with an 82% reduction in children referred to hearings on offence grounds (Extra funding announced to prevent youth offending | Law Society of Scotland) – meaning far fewer youth are even entering the system, thanks to robust community prevention. A flagship initiative is the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit (SVRU), which takes a public-health, community-engagement approach to youth violence. The SVRU is funded by the Scottish Government (~£1 million per year) and operates as an arm’s-length unit of Police Scotland (Scottish Violence Reduction Unit (SVRU) - Relationships Project). Rather than traditional policing, it funds streetworkers, school programs, and hospital “violence interrupters” to mediate conflicts. An independent evaluation credited the Glasgow VRU’s work with preventing an estimated 3,220 hospital admissions from violent assaults and halving the city’s youth homicide rate (How a pioneering Scottish violence reduction unit achieved radical ...) (How a pioneering Scottish violence reduction unit achieved radical ...). This illustrates how directing relatively modest funds into community-centric interventions (mentoring, counselling, dispute mediation) can yield large societal savings. Scotland also uses creative funding like the “CashBack for Communities” program, which takes assets seized from criminals and reinvests them into youth projects in disadvantaged communities. Since 2008, over £130 million has been committed to community initiatives through CashBack, funding 2.5 million activities and opportunities for young people nationwide (CashBack for Communities - Inspiring Scotland) (CashBack for Communities - Inspiring Scotland). This mechanism directly empowers grassroots sports clubs, arts programs, and mentorship schemes in areas most affected by crime, essentially giving communities the resources to solve the problems that spawn crime. The results in Scotland – steep declines in youth offending and custody – suggest that community-led interventions, backed by smart funding, can radically improve youth justice outcomes. Key best practices include: diverting kids from courts into community programs, convening local decision-makers (panels) to guide youth, providing nationwide funding support for local prevention work, and ensuring even serious issues like youth violence are tackled with multi-agency, not purely punitive, strategies.

Lessons for Queensland: Spain and Scotland demonstrate that shifting the balance of spending towards community and early intervention pays off. Queensland currently spends heavily on incarceration and reactive policing, yet experiences persistent youth crime. Adopting elements of the Spanish and Scottish models could guide more effective use of grants like Staying on Track and Regional Reset. Firstly, prioritise rehabilitation and relationships over detention – Spain’s success shows that treating young offenders with care, education and opportunity dramatically lowers reoffending. Queensland’s programs should incorporate education, vocational training, and therapy as core components (as planned), and ensure any residential facilities feel closer to school campuses or camp environments than prisons. Secondly, embed community decision-making and responsibility – Scotland’s example of Children’s Panels and community-driven initiatives suggests that local leaders and volunteers can play a powerful role in guiding youth. Queensland could establish regional youth justice committees (including elders, youth workers, victims’ representatives) to oversee referrals (much as the Reset referral panels will) and to hold programs accountable to community standards. Thirdly, funding should follow a justice reinvestment logic: invest in communities rather than in more cells. Both Spain and Scotland show far lower costs per successful outcome, because money is spent on support systems. By reallocating even a portion of the ~$1 million per-child annual detention cost (A Comparative Analysis of Youth Justice Systems in Spain and Australia) into schooling, healthcare, and housing for at-risk youth, Queensland can reduce crime more cost-effectively. Scotland’s Whole System Approach in particular highlights the importance of breaking silos – Queensland must coordinate Youth Justice with Education, Health, Child Safety, and community groups so that grants like Staying on Track link youth to all the services they need (mental health care, family services, mentoring, etc.). Finally, community-led funding mechanisms like CashBack for Communities could be emulated in Queensland. For instance, proceeds from crime or savings from reduced youth detention could form a fund that grassroots organizations can tap into for local crime prevention projects. This creates a virtuous cycle, empowering the very neighborhoods affected by youth crime to develop solutions. In summary, the international comparisons encourage Queensland to decentralize youth justice – both in philosophy and in funding – trusting communities and front-line practitioners to drive better outcomes, backed by government investment and oversight.

4. Cost Analysis – Administrative Overhead vs Community Investment

Current Spending Breakdown in Queensland: Queensland’s spending on youth justice has historically skewed towards costly custodial and centralised services, with relatively less on community-based prevention. This imbalance is evident in per-youth expenditure. In 2021–22, it cost roughly $2,162 per day to keep a young person in detention in Queensland () – that’s about $790,000 per year per child behind bars. By contrast, supervising a youth in a community program costs about $244 per day (). In other words, the state has been paying 9 to 10 times more to detain a young offender than it would to support that offender in the community. Despite this massive investment in detention ($218 million spent for an average 275 youths in custody per night (RoGS report: Queensland youth detention almost double any other state – Proctor) (RoGS report: Queensland youth detention almost double any other state – Proctor)), outcomes have been poor (over half reoffend within a year (RoGS report: Queensland youth detention almost double any other state – Proctor)). This indicates a lot of that spending is essentially administrative overhead of incarceration – maintaining facilities, security staff, transport, etc. – which has limited rehabilitative value. Indeed, a recent inquiry noted detention is the “most expensive and least effective” option for youth, often failing to address root causes () (). On the other hand, community investment (e.g. youth justice service centers, diversion programs) has been comparatively underfunded. Even with new programs, the government planned to spend $175m on Staying on Track and $50m on Reset over 4 years, against more than $200m per year on detention previously (RoGS report: Queensland youth detention almost double any other state – Proctor). The opportunity cost of this imbalance is huge – funds locked in high administration, low-impact uses (custody) could be freed for proactive solutions.

Administrative Overheads in Large Programs: Large institutions – whether government departments or big NGOs – inevitably have significant fixed costs that count as administrative overhead. In Queensland Youth Justice, a portion of the budget goes to central administration, regional offices, data systems, and management of service contracts. Past audits found inefficiencies such as duplicative efforts and money spent without clear evaluation (Reducing serious youth crime | Queensland Audit Office). For example, the state poured over $100 million into a “Youth Co-Responder” policing program from 2019–2027 (Reducing serious youth crime | Queensland Audit Office), which involves police and youth workers patrolling – a well-intentioned program, but one whose cost-effectiveness hasn’t been fully measured. If large NGOs become intermediaries for Staying on Track, they too will take an administrative cut (for HR, offices, etc.) out of the grant funds. It’s critical to scrutinise what percentage of funding goes to administration vs direct service. In similar social programs, it’s not uncommon that 15–25% of funds cover admin/overheads. At worst, as noted, some charities have had overheads exceeding 50% (Giving Guide | The Overhead Myth). For the new grants, if multiple layers of bureaucracy are involved (government contract managers, prime NGO contractors, sub-contractors), each layer could peel off a percentage. This cascading overhead can greatly diminish the “bang for buck” of taxpayer dollars.

Community Investment Yields Higher Impact per Dollar: Shifting funding to frontline community-driven work can greatly improve the impact per dollar spent. When money is used to hire a youth worker or mentor in a community, that staff can directly support dozens of young people – the effect is immediate and tangible. By contrast, money spent on a detention centre bed (which might sit empty if the population drops) or on layers of program administration produces far less direct benefit. Case studies illustrate the efficiency of community-focused models. In New South Wales, a justice reinvestment trial in Bourke (the Maranguka project) invested in local Indigenous-run initiatives for at-risk youth. An independent impact assessment by KPMG found it achieved a gross economic benefit of $3.1 million in one year against an operational cost of only $0.6 million – a 5-to-1 return on investment (Public policy shifts towards justice reinvestment). The savings came from reduced crime and fewer prison days, as youth offending dropped (e.g. juvenile reoffending fell by 39% in Bourke). This example shows that funding community programs (in this case, mentoring, family support, and youth activities led by local people) can dramatically reduce downstream costs like incarceration and policing. Every dollar put into the community generated multiple dollars in savings. Similarly, Scotland’s prevention efforts, which cost a few million per year, led to tens of millions saved by shrinking the youth prison population by two-thirds (Extra funding announced to prevent youth offending | Law Society of Scotland) (Extra funding announced to prevent youth offending | Law Society of Scotland). The cost per youth avoided is highly favourable.

In Queensland, recalibrating spending toward community interventions could yield similar dividends. For instance, the $217k it takes to detain one young person for 3 months could fund a full year of intensive case management and family support for several teens in the community. Even within the grants, ensuring minimal overhead will maximise impact: if an organisation receiving $5 million for a region keeps admin to 10%, that’s $4.5m going to services; at 30% overhead, only $3.5m hits the ground – a big difference in how many youth can be helped. It is therefore vital to track administrative vs program expenses in these grants. The Queensland Family & Child Commission has recommended redesigning spending toward community, noting detention is “the least effective way of addressing crime” and that community-based treatments both reduce reoffending and cost far less () (). Ultimately, by investing in communities – in people rather than in concrete and red tape – each dollar goes further. The new grants offer a chance to get more value: funding grassroots workers, community mentors, and local projects means the money circulates locally and addresses problems at their source. Queensland’s goal should be to invert the current ratio, spending the majority of funds on prevention and rehabilitation (which are high-return investments) and minimal on pure containment (which is high-cost and low-return).

5. Policy Recommendations

To ensure Queensland’s Staying on Track and Regional Reset grants achieve maximum impact, a series of policy and oversight measures should be implemented:

- Decentralise Funding and Decision-Making: Structure the grants so that local communities have a direct say in how funds are used. For example, establish regional advisory panels (including community leaders, Indigenous elders, youth representatives, and service providers) to co-design programs and oversee funding priorities. This follows the Scottish model of community panels and aligns with QFCC recommendations for diverse community expertise in youth justice decisions (). Decentralising decisions will make programs more responsive to local conditions and increase community buy-in.

- Prioritise Grassroots and First Nations Organisations: Ensure the grant process actively supports small and community-based organisations to access funding. This can include simplifying application requirements for small providers, offering capacity-building support, and breaking contracts into smaller lots where feasible. In regions with significant Indigenous youth, prefer or require partnerships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led organizations (as the RFQs have signalled in certain hubs (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf) (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf)). These groups are often best placed to engage disengaged Indigenous youth through culturally appropriate practice. A set percentage of funding could be reserved for community-run initiatives to guarantee grassroots share in the grants.

- Cap and Monitor Administrative Overhead: Introduce clear guidelines that limit administrative overhead for any organisation receiving these grants. For instance, cap non-program expenses at 10–15% of the budget, and require transparent reporting of how funds are allocated (salaries, admin, direct service, etc.). The government should closely audit expenditures to ensure funds are not being lost to excessive admin or executive salaries. Payment milestones can be tied to service delivery targets rather than simply time elapsed, to push agencies to deploy funds to the field quickly.

- Outcome-Focused Contracting with Accountability: Build in strong accountability for results so that large providers cannot rest on their laurels. Contracts for Staying on Track and Regional Reset should include key performance indicators such as number of youth engaged, completion of programs, educational or behavioural outcomes, and ultimately recidivism reduction. As the QAO suggests, funding should be contingent on outcomes wherever possible (Reducing serious youth crime | Queensland Audit Office). Publish annual outcomes for each region and provider to introduce public transparency. If one provider is not achieving impact (e.g. youth under their program continue to reoffend at high rates), consider recompeting that contract or reallocating funds to alternative local partners. This performance-based approach will incentivise providers to truly prioritise youth outcomes over bureaucracy.

- Regular Market Testing and Diversity of Providers: Avoid long, auto-renewed contracts with single providers. Instead, regularly open the grants to competition (for example, every 3–5 years) to invite innovative proposals from different organisations. The QAO found the department previously failed to test the market, risking poor value for money (Reducing serious youth crime | Queensland Audit Office). By refreshing the pool of providers periodically, new community groups or coalitions can emerge with creative approaches. Even within the program, allow multiple providers per region if needed (the RFQ permits more than one contract in a hub (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf)), so that a small specialist NGO could serve a particular cohort (for instance, a local Murri youth group working alongside a larger NGO in the same area).

- Embed “Justice Reinvestment” Principles: Use savings from any reduction in youth incarceration to reinvest in community programs. As community-led efforts succeed and detention numbers fall, calculate the cost savings and channel those funds into a grant pool for grassroots prevention (similar to Scotland’s CashBack for Communities model funded by crime proceeds). This creates a positive feedback loop – success leads to more resources for further success. Even now, Queensland could pilot a Justice Reinvestment initiative in a high-needs community: allocate a set amount (say, $5 million) to that local community to design its own youth crime prevention action plan, then rigorously evaluate outcomes (following the example of Bourke, NSW, which yielded a 5:1 benefit-cost ratio (Public policy shifts towards justice reinvestment)).

- Strengthen Oversight and Reduce Red Tape: Government oversight should focus on big-picture outcomes and financial propriety, while avoiding micromanaging the day-to-day. Streamline reporting requirements so providers spend more time delivering services and less time writing reports – for example, unify the reporting platforms (the department’s Procure to Invest system will be used (DYJSV-0004_RFQ_Regional_Reset.pdf)) and perhaps provide a monitoring officer to assist smaller orgs with compliance. At the same time, maintain a robust evaluation framework. Commission independent evaluations of Staying on Track and Regional Reset at regular intervals (e.g. after 2 years and 4 years) to measure effectiveness and gather lessons. Involve community feedback in these evaluations – the real test is whether local families and youth feel the impact. If an approach isn’t working, be prepared to redirect funding to approaches that are (for instance, if a residential camp model has low completion or poor outcomes, pivot to more family-based support or other models, as evidence dictates).

- Integrate Services and Wrap-Around Support: Leverage the grants to improve service integration on the ground. Grassroots organizations often excel at holistic support but may need backing from government systems. Use policy levers to ensure that no young person falls through gaps – e.g., guarantee priority access for program participants to drug treatment, mental health services, housing, and schooling. Formalize local protocols between youth justice services and schools, employers, and sporting clubs to create pathways for youth. This kind of “wrap-around” approach amplifies the effect of funding by enlisting existing community assets (schools, businesses, volunteers) in the mission. Essentially, make Staying on Track and Regional Reset not stand-alone programs but catalysts for a wider community effort to support at-risk youth.

By implementing these recommendations, Queensland can transform its investment into real outcomes. The overarching theme is to put authority and resources in the hands of communities and frontline practitioners – those closest to the problem – while the government shifts to an enabling and auditing role. This means trusting smaller organisations with funding, holding larger ones to high standards, and constantly checking that dollars are reaching kids in need, not vanishing into bureaucracy. Early signs are positive (the inclusion of Indigenous providers, outcome monitoring plans, etc.), but continued vigilance and adaptation are needed. With smarter grant distribution and oversight, Queensland’s ambitious programs can truly “stay on track” – delivering safer communities and brighter futures for young people, rather than just more headlines and sunk costs.

Sources:

- LNP policy announcement on Staying on Track (2024) – recidivism statistics and program description (LNP - Liberal National Party of Queensland (LNP)) (LNP - Liberal National Party of Queensland (LNP)).

- Qld Dept of Youth Justice Industry Briefing – funding commitments and initiative overviews (Youth Justice Power Point Presentation) (Youth Justice Power Point Presentation).

- Qld Youth Justice RFQ Documents (2025) – regional funding allocations and procurement requirements (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf) (DYJVS-0015_Staying_on_Track-Request_for_Quote.pdf).

- Qld Family & Child Commission submission (2023) – cost of detention vs community supervision, efficacy of non-punitive approaches () ().

- Queensland Audit Office Report (2024) – findings on youth justice program funding, procurement and contract management issues (Reducing serious youth crime | Queensland Audit Office) (Reducing serious youth crime | Queensland Audit Office).

- Law Society of Scotland news (2018) – impact of Scotland’s Whole System Approach (82% drop in youth offending, etc.) (Extra funding announced to prevent youth offending | Law Society of Scotland).

- Justice Reform Initiative (2023) – comparative youth justice costs (Australia >$1M per child/year vs Spain €70k with <15% recidivism) (A Comparative Analysis of Youth Justice Systems in Spain and Australia) (From Punishment to Potential: Lessons from Spain's Innovative Youth Justice Model - Day 1 with Diagrama).

- Justice Reinvestment case study (Bourke, NSW) – economic impact of community-led interventions (5:1 return) (Public policy shifts towards justice reinvestment).

- Scottish Government – CashBack for Communities program data (£130m to community youth projects since 2008) (CashBack for Communities - Inspiring Scotland).

- The Sentencing Project report (2021) – evidence that community-based alternatives reduce recidivism compared to incarceration (Effective Alternatives to Youth Incarceration – The Sentencing Project).

.png)

.png)

.jpg)